[idolatry and repetition: from simulacrum to gnosis]

In one of his poetic turns, Heidegger rejects the dichotomy of word and image, which in the German tradition was understood as meaning that images required space in order to be perceived, while words required time. To Heidegger, the truth of language - poetry - is image and therefore space par excellence; images, in turn, incorporate time in the form of the invisible - the truth of an image is not in the representation of the seen as conventionally understood, but in invoking what is outside itself, the 'thingness' of things, the hidden part - perhaps what Barthes calls punctum.

The reference to what is outside the immediate field of vision yet implicated in the image finds an inverse counterpart in Baudrillard's comments on photography as 'exorcism': "If something wants to be photographed, that is precisely because it does not want to yield up its meaning; it does not want to be reflected upon. It wants to be seized directly, violated on the spot, illuminated in its detail. If something wants to become an image, this is not so as to last, but in order to disappear more effectively."

Kafka, in a similar vein, equates this to writing: "We photograph things in order to drive them out of our minds. My stories are a way of shutting my eyes." The image at hand, whether a visual image or a sentence-image (to use Ranciere's term), is a fixed or bare repetition, the Platonic repetition of the same, the copy which is always haunted by the spectre of an original but which, precisely for this reason, is false, and can never truly repeat the Idea (per Deleuze), the 'thingness' of a thing. As Baudrillard puts it, "to make an image of an object is to strip the object of all its dimensions one by one: weight, relief, smell, depth, time, continuity and, of course, meaning". To this Deleuze counter-poses the simulacrum, the real repetition of the Nietzschean eternal return which is never repetition of the same. Real repetition is where the new emerges in nature.

Far from empty theoretical posturing, what this broadly evokes borders on the atavistic: in virtually every major religion there is some kind of prohibition or taboo related to visual representation - idolatry, the making of graven images, the depiction of the prophet, etc. The fact that such norms are rarely observed, at least in the strictest terms, by the mainstream forms of institutionalized religions is evidence of a tension - an internal difference - at the heart of religious traditions. The Heideggerian poetics taken up by Baudrillard and Kafka hints at an ancient gnostic principle abandoned by theologians and organized religions in their gradual transition to rationalist modernity.

Even Heidegger's rejection of the split between word and image can be accomodated within a gnostic framework. The prohibition on 'taking the Lord's name in vain', or even more explicitly, the Hebrew prohibition on writing it down at all, alternately insisting that the name, if written, be stripped of vowels (YHWH), aims precisely at this. What is holy cannot be imagined, represented or fixed in any way, and this applies to visual image and text alike. In order for it to be present, it must remain immanent. The gnostic God, to put it in Deleuzian terms, is the ultimate 'dark precursor', the differenciator of differences, the object=x which ensures the communication between disparate series by never being in its proper place, remaining a void.

An exhibition at the Centre Pompidou in Paris a few years ago explored this very aspect of the visual image - entitled Voids, the exhibition was a retrospective of empty exhibitions over the past 50 years, starting with Yves Klein's 1958 exhibition of an empty gallery space at the Galerie Iris Clert. Empty space features as a platform for envisioning the invisible, for contemplating space in time, opening our eyes to the 'thingness' of things, their absence. It is a way of repatriating the exorcised content of the captured image, releasing the violated image back into the void, redeeming the holy.

It it this dimension again that is activated in Chinese artist Zhang Huan's "Berlin Buddha" - a performance-art piece in which a buddha sculpture made of concrete was ripped apart and reduced to dust in front of the gallery audience. This reference to the buddhist notion of 'killing the buddha' also hints at a shared element of gnosis that traverses a whole range of philosophical and religious traditions - from the Pagan ritual of the 'May King' or 'killing the god' to the Adonis myth (which echoes the earlier Sumerian 'Tammuz' and a number of other ancient myths of death/rebirth), the Crucifixion of Christ, etc. The very existence (as opposed to Being) of 'God' in any sense - as statue, flesh-and-blood, even ghost or spirit - is an imaging, a fixation, and therefore sacrilege.

Where the Kafka/Baudrillard gnostic indictment of the image and Heidegger's poetics part ways is in that Heidegger does not exclude the possibility of an authentic image. In Baudrillard's gnostic vision, the image is by necessity representation and therefore loss. But this seems too easy a dismissal for Heidegger - it is possible for an image to evoke the thingness of things, to show without representing.

It may be precisely this that makes Diane Arbus' photographs unique: it seems all too simple to say that she portrayed 'freaks'. Her uniqueness is that in her photographs, 'freaks' - giants, dwarves, transvestites, circus performers, those on the fringe of ordinary society - appeared normal, at home with themselves, ordinary; whereas the 'normal' people (i.e. couple with child strolling down 5th avenue) appeared unsettled, out of place, weird, plastic.

One shouldn't mistake this overarching theme in Arbus' work as a gesture of equation: the photographs form two distinct series. The common term between them, repeated in each series - 'freak' for lack of a better term - far from being an identity or similarity between them, is precisely what grounds their difference, what distinguishes the two series. It is the object=x, the 'dark precursor', the differenciator of differences. It establishes a point of contact between them, differenciates them, while remaining invisible, or outside the frame and without any positive content: one cannot locate it ('freakishness') precisely or explain its meaning, but it is there nevertheless, running silently througout each series. Through this displacement and repetition Arbus' photographs evoke something truly new, carving out a unique territory among images.

It is no surprise that, in her senior high school yearbook where each student was asked to provide, as a caption for their graduation photo, a statement about their goals in life upon graduating, among all the boring statements by her fellow students on career and marriage aspirations, Arbus stood out like a sore thumb with these words: "To shake the tree of life and bring down fruits unheard of."

[common humanity and resistance: quo vadis, domine?]

The first time Christ is crucified, he is merely a holy man who gives up his life for the sake of another, only one among many Judeans killed by the Romans in this gruesome manner. It is only with the second crucifixion - the repetition - that the truly new emerges, and the historical figure of Jesus of Nazareth is transformed into Christ, the redeemer - it is only the second time, with a second death, that 'God' truly dies on the cross.

The dark precursor is thus constituted retroactively (per Deleuze), and 'God' - the object=x - emerges as the invisible differenciator between the series, establishing a point of communication between them but without an identity or similarity; 'God' is the pure difference between series that repeat one another, the new that emerges in each repetition. It is the 'esoteric word' that ensures communication, while establishing against the background of the 'same' the difference between each series: the spiritual 'killing of the Buddha', the pagan ritual of spring ('killing the May King'), the crucified flesh-and-blood God of Christianity.

In this sense, the revolutionaries of the Arab Spring and Iranian revolts - in opposing state/religious authority from a position of faith (in many cases), referencing religious tradition - set out from the position of Antigone/Jesus. Rather than simply resistance, Antigone's position in ethical terms circumvents state authority (Creon) to establish a direct relation to a higher authority beyond the state ("the unwritten laws of heaven…"); in much the same way, Jesus opposes the Roman empire by appealing to the 'Kingdom of God'.

This is perhaps the result of Walter Benjamin's insight that state authority rests not on a 'rule of law' but on rule by 'exception' or whim, disguised by concepts such as 'the rule of law'. If the 'rule of law' can be suspended whenever it proves inconvenient to those in power, it becomes questionable whether it ever was an authentic principle or modus operandi. Within these parameters, the form that an authentic resistance must take, rather than operating within this farcical system of rules and rights granted by the state, is to invoke an authentic exception, as Benjamin puts it - an 'unwritten' authority beyond the state - and destroy the law as such, clean the slate.

This theological dimension cannot be underestimated in the context of the struggle in the Arab world, for what may be obvious reasons: by invoking the internal difference, the Egyptian or Iranian protesters' insistence on faith, far from indicating a 'lesser evil' or reformist moderation, radically lays bare the real struggle - not between Western liberal democracy and Islam, but between the authentic personal faith of gnostic populism on one hand, and the inauthentic authoritarian faith of those in power, on the other. They share a term - Allah - but this shared term is an emptiness that in fact differenciates them and splits them apart, their 'dark precursor'. It is the same struggle that goes on worldwide, traversing systems and religions.

In her essay on Hegel and Haiti, Susan Buck-Morss relates the story of a contingent of French soldiers sent by Napoleon to put down the slaves' revolt; upon hearing a group of former slaves sing the Marseillaise (which in one verse denounces "l'esclavage antique"), the Frenchmen decide not to ambush the rebels, laying down their own weapons and wondering aloud if they aren't fighting on the wrong side. Their faith - in the ideals of the French Revolution - is authentic. "Common humanity appears at the edges," Buck-Morss concludes. Power comes from below.

If I may digress a little, to quote at length from Tolstoy, War and Peace: "in order that the will of Napoleon and Alexander (on whom the event seemed to depend) should be carried out, the concurrence of innumerable circumstances was needed without any one of which the event could not have taken place. It was necessary that millions of men in whose hands lay the real power - the soldiers who fired, or transported provisions and guns - should consent to carry out the will of these weak individuals, and should have been induced to do so by an infinite number of diverse and complex causes."

Asserting further that the major historical players are in the end far more caught up in the inertial momentum of history than the people they command, Tolstoy concludes, "A king is history's slave."

By contrast, in the words of Salvador Allende, "La historia es nuestra y la hacen los pueblos." It is the people who make history, whether they know it or not.

The fundamental opposition here - between the unwritten and the written, between the sacred/holy and the concrete/fixed, between the raw, volatile will of the people and established state authority - invokes what Deleuze refers to as the only real opposition in nature: between the Idea and representation. Real difference is always internal, and it goes all the way down - this is precisely the consequence of Heidegger's insight that words, through poetry, can create images, and that images in turn can express absence; like the wave/particle duality in quantum physics, the split between word and image is internal to both word and image. In the words of Walt Whitman, "I and mine do not convince by arguments, similes, rhymes; We convince by our presence."

Or as Louis Armstrong - jazz gnostic - put it, when asked how he would explain to the uninitiated what jazz music was all about: "some people, if they don't know, you just can't tell 'em."

(The idea of jazz, beyond even the boundaries of genre or music as an art form, embodies in the purest sense the notion of repetition=difference.)

Not to miss out on a more contemporary pop culture reference when it rears its pretty little head - I've never found the song 'Royals' that interesting, despite its appropriation by Bill de Blasio in his progressive campaign for New York Mayor - musically and lyrically, 'Team' is Lorde's real gem, with this lyric especially:

We live in cities

you'll never see on the screen

Not very pretty, but we sure know

how to run things

Living in ruins

of a palace within my dreams

And you know

we're on each other's team

It's those cross-connections again, that cut across cultures and make visible the real differences, and real allegiances - like the French soldiers and Haitian slaves singing the Marseillaise, the Syrian rebels and Bostonians exchanging messages of solidarity, or the Tahrir Square protesters in Egypt holding signs saying 'we stand with the people of Wisconsin' in the middle of Governor Scott Walker's union-busting campaign. We're on each other's team. We live in cities you'll never see on the screen - the revolution will not be televised, as Gill Scott-Heron famously put it.

* * *

"What becomes established with the new is precisely not the new," (Deleuze) and this is one of the pitfalls of any revolutionary struggle. A revolution can never establish itself or insinuate itself in laws and institutions, let alone state organs; it cannot make an image of itself - the revolution will not be televised. It is in this sense that effective resistance to state authority, by invoking an authentic exception, must rely on Benjaminian 'divine violence' - divine because it is 'unwritten', because it cannot inscribe itself in (written) law. In order to remain vital, revolution must remain a threatening presence, a force of nature, a pure momentum poised against organs of authority as such; its function - and its everlasting hope - can only ever be to set in motion a wheel of critical mass when necessary, to produce complex repetitions out of which emerge authentic differences, to perpetually "shake the tree of life and bring down fruits unheard of."

Tuesday, 29 April 2014

The Revolution Will Not Be Televised: Gnosis as 'Dark Precursor'

Monday, 20 April 2009

Constructivism and the Future

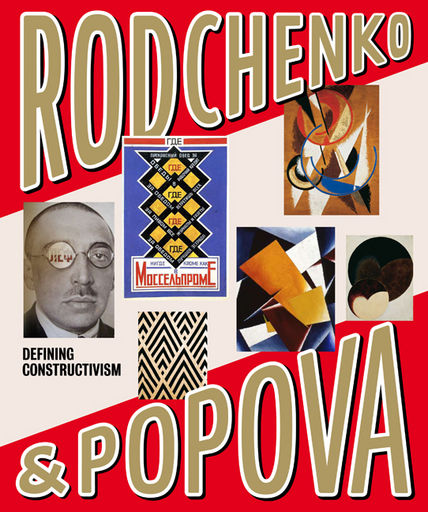

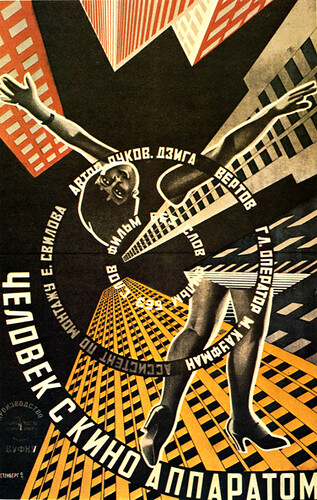

Far more refreshing than the 'Altermodern' Triennial at the Tate Britain, the special exhibition at the Tate Modern, 'Rodchenko and Popova' provides a comprehensive but by no means nauseating retrospective on the art of the revolution, as it flourished before the thermidor of Socialist Realism. If any 20th century art movement should be revived and rethought, I say, it should be Russian Constructivism.

In fact if, as Zizek says, the future will be either socialist or communist - 'socialist' meaning the kind of nanny-state capitalism practised by Western governments in the wake of the financial crisis - for the art world this must mean that the future will be either Altermodern or Constructivist. Art will either remain more or less what it is, a distinct sphere of rationality backed up by specific forms of cultural practices and modes of communication, or it will be sublated in a multidisiplinary network within an overall revolutionary dissolution of separate social spheres and disciplines.

'Altermodern' is clearly the tendency to be opposed, but not so much for the content of the art it takes under its wing - a lot of which, as discussed earlier, can be described as 'postmodern', in spite of its curator Nicolas Bourriaud's proclamation that 'postmodernism is dead' (kind of like Leonard Cohen's lyric... "I fought against the bottle/but I had to do it drunk..."). What should be opposed is not the art but the critical tendency - the mentality of 'out with the old, in with the new' - exemplified in equal measure by buzzwords like 'Altermodern' and by the spectre of Wall Street's return to Marx. ('retro' is now the 'in' thing...)

The issue is not that these are mere 'surface effects' but precisely that they exhibit the opposite or inverse tendency of 'depth without breath', of getting to the bottom of a problem but only after the fact, only when the damage is already done. Why did we need a complete breakdown of the system in order to correct its course, if it is at all a correction? (I personally don't find the idea of bankers reading Das Kapital very convincing.) Or why did we need a total degeneration of the art world into a commercial meat market in order for someone to suggest something is wrong?

What is needed is not merely a new form of art - let alone a new buzzword, a new name, a new way forward or into the depths - but a new way of thinking about the very production process of art and its social function, something which the constructivists, unlike most art movements, sought to do. What is needed is precisely not more depth, nor a different kind of depth, but more breadth: the extension of art into other realms. Let's face it: to what extent does Bourriaud's theorizing really exhibit the traces of a 'universal language'? Isn't the work of "translation" at stake in this 'altermodern' phenomenon merely the transcription of a myriad of untranslatable cultural phenomena into one non-universal and even somewhat esoteric language particular to the foofy contemporary art circuit, and largely unintelligible to the majority of society globally?

The language of lines and forms, on the other hand, is a universal language - if for no other reason than what one could call its 'primitivism'.

Constructivist design for a cup and saucer

But even more so, an art that rejects the notion of "art for art's' sake", an art that believes art must be put to use - in addition to the promise of social change built into its very core and fibre, must speak a universal language in order to exist. It can only exist on condition of extending its breadth, of its expansion into 'non-art'.

At the same time, the constructivist egalitarian rejection of the term 'artist' in favour of 'constructor', the simplification of the process of creation, to demistify art, etc - hints at the postmodern 'death of the author'; in both cases the aim is to undermine the privileged position of the speaker/author/artist as the arbiter of meaning or aesthetic value in favour of a configuration where the very dichotomy of author/consumer becomes false. Art for the people.

In this context the reference to 'modern' in 'altermodern', and the call "death to postmodernism" can be read as the thermidorian gesture of restoring order, repeating Stalin's gesture of outlawing constructivism and proclaiming Socialist Realism as the only acceptable form of art.

Constructivist clothing design: clearly the future

Another thing worth thinking about is the constructivists' involvement in advertising, and their insistence on not rejecting it as a capitalist consumerist ploy. There is something to this: for how can one confront the phenomenon of advertising at all, if not with advertising itself - either in the form of subversive re-production (i.e. Adbusters) or in the form of counter-advertising, advertising for the right causes?

The Adbusters slogan for what they have dubbed 'Buy Nothing day', November 22, has a distinctly constructivist ring: MAKE SOMETHING - BUY NOTHING.

From now on, I am no longer the author of this blog, but its chief constructor.

Wednesday, 15 April 2009

Punkstmodernism is not dead: notes from behind the irony curtain

I hate it when people declare something 'dead' when it's actually not.

Scratch that. I hate it when people say that an Idea is dead, period. Sure, there are dead ideas; but that's because they never were real Ideas, because they were born dead. Just like "manuscripts don't burn" - Ideas don't die. In the world of Ideas, the only things that can ever legitimately be declared 'dead' are those that never were - the many false starts, misapprehensions, misdirections in the history of human thought. Ideas do not oscillate between the living and the dead; they oscillate between the living and the stillborn. Confusion slips in when the latter go on 'living', Zombie-like, 'undead' - until centuries later some rare, clear-sighted specimen of our blundering race sees through the folly, and tells it like it is.

Sadly enough, Nicolas Bourriaud - art critic, curator, and co-founder of the Palais de Tokyo - is no such gent, and he doesn't tell it like it is. Postmodernism is not dead. It is alive and kicking, and there is nothing radically new here. Postmodernism, like every great idea, has been declared dead before - most notably after September 11, when neoliberal apparatchiks excitedly whispered that the 'age of irony' was over. In fact, Derrida's strain was even declared 'dead on arrival', years ago, before the term 'deconstruction' embedded itself in the vocabulary of art and philosophy to the point of becoming a cliche.

The thing about irony is that - like dialectics - it just never goes away. It's worse than cancer. The more you 'excise' it, the more it multiplies - the more ironic the irony gets.

When people do declare an idea to be dead, this does signal a change, but it is often not the change they are counting on - it is very often the contrary. Just when Francis Fukuyama announced the 'end of history' in the Final Age of liberal democracy, he himself soon withdrew the proclamation. Just when it looked like Global Capitalism was going to be the only game in town for good after the fabled 'fall of communism' in the 90s and the various proclamations that the 'age of ideologies' was over, the financial system collapsed and people started reading Marx again.

And just as Nicolas Bourriaud proclaimed that 'postmodernism is dead', postmodernism reared its little head all over the very exhibition that Bourriaud curated this Spring at Tate Britain to signal the death of postmodernism and the birth of what he has dubbed 'altermodern'. Isn't that, like, ironic?

I did like some of the works I saw, but I didn't find the show as a whole especially refreshing as against the contemporary art scene today. But rather than comment on the merits here, I will only address a few examples in relation to ('postmodern') theory. All quotations addressing the works and artists in the Triennial are from the exhibition guide.

Tacita Dean's work 'The Russian Ending' 2001, one of the highlights of the exhibition, is inspired by an early twentieth century custom in the Danish film industry where each film was produced in two versions: a happy one for the American market, and an alternative with a depressing or tragic ending for the Russian market. Taking images of disasters from original postcards purchased in flea markets, Dean uses handwritten notes that suggest the storyboard of a film to provide "imagined endings to imagined films."

What Dean is clearly getting at is the ambiguity of meaning in text and narrative that this reference to the Danish film tradition evokes; she inserts, for instance, coy double entendres such as 'man's laughter/manslaughter' - play, irony, reversal of signs. How is this in any sense not postmodern? Decontextualizing/recontextualizing images to imbue them with a meaning unimagined by their authors, through writing - palimpsest - and moreover suggesting "imagined endings to imagined films", is this not post-modernism par excellence? A perfect example of - whatchamacallit - deconstruction?

Similarly, Peter Coffin's work 'Untitled (Tate Britain)' 2009, projects animations with soundtracks onto existing artworks from the Tate's collection. The works "remain both in their conventional habitat and simultaneously become mobilised as fictitious characters in a new narrative scenario which...opens up a web of associations." In this way, Coffin "charges existing artworks with a life and mind of their own."

Oh, you mean that whole thing about the "death of the author" - how the 'meaning' of a work/text/utterance does not reside simply in the mind of the original speaker/author? Yep, nothing new there. Derrida again, right? And a bit of Barthes?

Rachel Harrison "splices together found objects, images, and hand-sculpted abstract forms to create installations that possess the iconoclastic energy of Punk...presents all her material on an equal footing and wilfully flattens out any cultural hierarchies." If that doesn't sound 'postmodern' enough, her work in the exhibition, 'Voyage of the Beagle, 2007', a "pantheon of fifty-eight portraits of figures and sculptures, from ancient artefacts to shop mannequins" - including a pelican, a buddha statue, a bear, an Elvis mannekin, a bear, a superman blow-up doll, all shot and framed identically and hung in a series - "functions as a sort of anti-taxonomy, mocking ideas of progression or systems of classification and otherness."

This anti-taxonomy is what Michel Foucault would refer to as a 'heterotopia' - an impossible place where all the unclassifiable junk is secluded in order to make a 'utopia' of order and reason (and taxonomy) 'possible'. Except that in The Order of Things - a work emblematic of precisely Foucault-the-poststructuralist - he goes even further. Harrison's work is just not radical or probing enough. A major inspiration for Foucault, cited in the famous introduction, was a short story by Jorge Luis Borges - a 'modern' writer (more on that below) - in which he mentions a "certain Chinese encyclopedia" which divides animals into

"(a) those that belong to the emperor; (b) embalmed ones; (c) those that are trained; (d) suckling pigs; (e) mermaids; (f) fabulous ones; (g) stray dogs; (h) those that are included in this classification; (i) those that tremble as if they were mad; (j) innumerable ones; (k) those drawn with a very fine camel's-hair brush; (l) etcetera; (m) those that have just broken the flower vase; (n) those that at a distance resemble flies."

This passage, to Foucault

"shattered thought...breaking up all the ordered surfaces and all the planes with which we are accustomed to tame the wild profusion of existing things...to disturb and threaten with collapse our age-old distinction between the Same and the Other...Moreover, it is not simply the oddity of unusual juxtapositions that we are faced with here...like the umbrella and the sewing machine on the operating table. The monstrous quality that runs through Borges's enumeration consists, on the contrary, in the fact that the common ground on which such meetings are possible has itself been destroyed...A vanishing trick that is masked or, rather, laughably indicated by our alphabetical order...What has been removed, in short, is the famous 'operating table'."

Another work, Simon Starling's 'Three White Desks', is made up of three copies of a no longer existing desk designed by Francis Bacon for Australian writer Patrick White. Only the first desk is a copy of it in fact, made by a cabinet maker after the only surviving photo. The second one, made after an identical photo of the first desk, is a copy of a copy, and is in turn photographed...you get the picture. The third desk is a "copy of a copy of a copy."

The disavowed reference is clear - Warhol only did it better, with more umph. The added dimension in Starling's 'altermodern' approach is having each copy made by a different cabinet-maker in a different country, each in a city relevant to the story of the original desk. But this unnecessary step, which makes for an 'interesting story', only obscures the key point - that repetition alone produces change, without any added input. If one artist alone makes copies of a thing, by the same method, in the same medium - after a sufficient number of repetitions the copy becomes a simulacrum. Each repetition brings about a change, however minuscule. This work, then, tells us nothing significant about 'cultural exchange' and 'translation' between cultural milieus or mediums - every copy, every repetition is a 'translation', every work - every copy in fact - a 'cultural milieu' unto itself on a microcosmic scale.

Here's Deleuze, one of the, you know, key dudes of postructuralist/postmodern philosophy, writing about Warhol circa 1968, p 366, Difference and Repetition [my italics]:

"Each art has its interrelated techniques or repetitions, the critical and revolutionary power of which may attain the highest degree and lead us from the sad repetitions of habit to the profound repetitions of memory, and then to the ultimate repetitions of death in which our freedom is played out...the manner in which, within painting, Pop Art pushed the copy, copy of the copy, etc., to that extreme point at which it reverses and becomes a simulacrum (such as Warhol's remarkable "serial" series, in which all the repetitions of habit, memory and death are conjugated)..."

I rest my case.

Reading Bourriaud's introductory text I find myself baffled - it oscillates between totally meaningless commercial art-world jargon with no apparent relationship to most of the works in the exhibition, other than what could be said of any contemporary art ("the figure of the artist as homo viator, a traveller whose passage through signs and formats reflects a contemporary experience of mobility"); and a schoolboy's highly simplified rendition of precisely postmodern philosophy, i.e. Deleuze - "lines drawn both in space and time, materializing trajectories rather than destinations, expressing a course or a wandering rather than a fixed space-time"; the term 'altermodern', he tells us, "suggests a multitude of possibilities, of alternatives to a single route."

Très chic. Yet this somehow means that the "historical period defined by postmodernism is coming to an end"? Not with these kinds of contradictions to play with.

Derrida can be read into this discussion as a kind of arch-Marxist: where Marx saw internal contradictions in capitalism, Derrida saw internal contradictions everywhere. Deconstruction is internal to things - and this is what bugs me when people throw these words around without grasping them, and write stuff like 'Artist so-and-so uses conceptual approaches to such-and-such to deconstruct notions of this-and-that with reference to narratives of something-or-other', and so forth. People don't deconstruct anything - deconstruction is a passive process, a force of nature. It can only be shown - one can only draw attention to the self-deconstruction of, say, a text. Things deconstruct themselves, break down into their constituent components, expose their own contradictions, generate their own opposites and internal differences. Language deconstructs itself through repetition. Ideas deconstruct themselves. Modernity, too, deconstructs itself; and Bourriaud's 'Altermodern' triennial is a case in point.

'Altermodern' decomposes, ironically enough, into a poor copy of 'postmodern'. And by 'poor' I don't mean artistic merit or 'faithfulness to original', but quite the contrary - poor in the sense that it falls short of its own mark, that within a history of thought, it doesn't represent a development in the way in which 'postmodernity' was a development of 'modernity'.

One of the great lessons of one of the key philosophers of modernity, Hegel, was this: something that appears to be refuted - annihilated - in the progression of thought, is merely sublated. (Aufhebung) One of Hegel's favourite metaphors was that of a flower springing from a bud, appearing to destroy the bud in the process; the flower blooms, the bud disappears. Nevertheless, without the bud there would be no flower - it is the bud that gives birth to the flower, and remains sublated within it.

Postmodernity is a moment in the history of thought - one of its key realizations as against modernity being that meaning and language are inherently unstable; that identity is unstable; that concepts themselves are unstable and their meanings shift, evolve. Even terms like 'modern' and 'postmodern' or 'poststructuralist' are themselves inherently unstable, and were rarely - if ever - self-applied by those thinkers usually corralled under them by high-minded critics concerned with fads and fashionable phrases.

We cannot simply retreat from that, abandon that moment in thought, pretend it didn't happen. In Deleuze, the dialectic exemplified in Hegel's metaphor translates into becoming. But becoming - what Bourriaud might call "trajectories rather than destinations" - encompasses more than Hegel's dialectic because Deleuze, among other things, had Darwin and evolutionary science behind him. Becoming takes account not only of a process of growth in the sense of a single living organism (even as a microcosm of world spirit), but the whole process of genetic development and actualization, which adds complexities - is more in the vein of 'rhizomatic'. It can move and split in any direction and does not follow any clear, determinable path to 'Progress' but only adaptation, neither up nor down, neither forward nor back; and it is dependent precisely on processes of repetition - the copy of a copy of a copy, etc - which over time generate the truly new in nature.

To Deleuze, the very suggestion that there is an opposition (real or apparent) between 'bud' and 'flower' as distinct identities, and that one annihilates or even appears to annihilate the other, would be false: this is the field of the negative, the 'false problem' or 'the fetish in person'. The one, rather, becomes the other, morphs into it. Together they form a 'trajectory' rather than two 'destinations' or 'points'.

In this vein, I find Bourriaud's notion of 'altermodern', at least from what I have so far seen in practice, very un-becoming.

Altermodernity hasn't come up with any truly new problems in relation to postmodernity. To use Bourriaud's own terminology, what he has missed is that the relation modern-postmodern is precisely that - a relation, in which neither is a fixed point in space/time - the two form a trajectory in which neither can be reduced to simply itself, or disengaged from the other.

Ideas - real ideas, generating real problems - don't die; and many of the pieces in the 'altermodern' exhibition demonstrate that the Idea in question here - the 'postmodern' one - is very much a real Idea, embodied in actual objects, even ones whose authors or curators claim that that same idea is 'dead'. Irony is indeed alive and well.

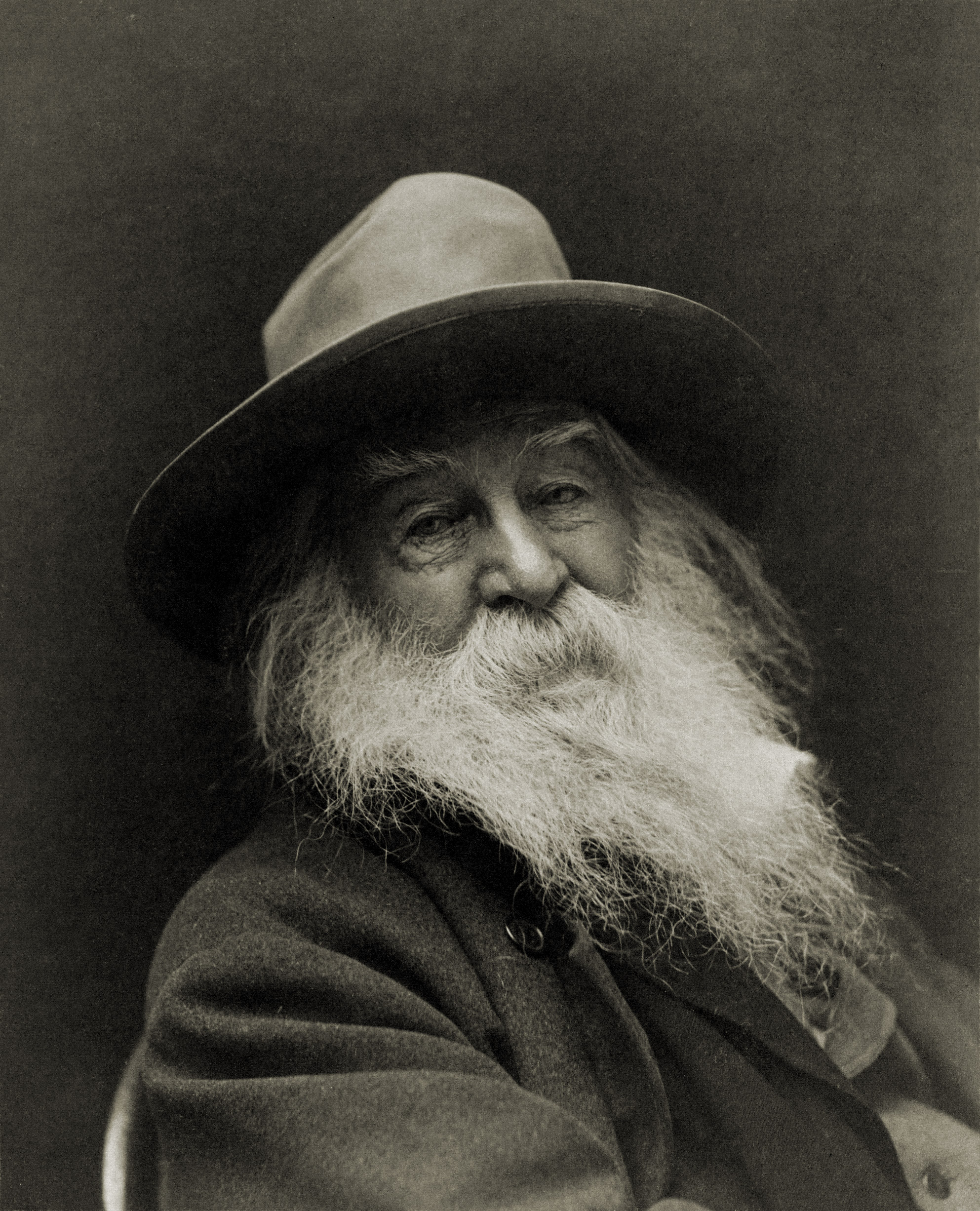

The thing is, writers and poets always 'got it' before art critics and historians did. Rimbaud's famous remark in a letter to a friend - Je est un autre ('I is another') - has long been mulled over as a herald of postmodernity. Jack Kerouac's "it ain't whatcha write, but the way 'atcha write it" hints at the notion of différance. Yet another great poet once wrote

Do I contradict myself? Very well then

I contradict myself.

I am large, I contain multitudes.

Now that sounds pretty damn post-modern to me. When was it written? 1855. Walt Whitman.

In the case of some writers, who stand in the margins and evade easy pinning down, such as the Portuguese Fernando Pessoa, people have debates and ask: was s/he modern or postmodern? And I say to that: does it matter? Only the Ideas matter in the end. Where 'modern' stops and 'postmodern' begins is a matter of pointless pedantry.

Walt Whitman - clearly postmodern

These writers - Foucault included - themselves embody that trajectory in thought, the discovery - the transition from 'modern' to 'postmodern'.

I am tempted to speculate here that Bourriaud may in fact have a point, however not the one he figures - that perhaps the rise of fads and buzzwords like 'altermodern' in today's global financial capitalist world does signal a new era, but one which is still postmodern, even ultrapostmodern rather than 'altermodern'. What we may be faced with here is a stripped-down version, a 'bare repetition' of postmodernity without self-awareness, or with a kind of false consciousness - a thoroughly unhinged postmodernity unaware of its own historical moorings, under a different name, a different guise. An even more postmodern postmodernity, precisely because it doesn't call itself that. (very much in line with Zizek's remark that one of the dangers of today's global capitalism is that it 'no longer calls itself capitalism.') Postmodernity, in other words, is Altermodernity's unnameable core - its Big Other - the elephant in the room.

So, there - deconstruct that.

As another modernist poet - whose words also have a distinctly post-modern/Taoist ring at times - T.S. Eliot, put it:

Is only a shell, a husk of meaning

From which the purpose breaks only when it is fulfilled

If at all. Either you had no purpose

Or the purpose is beyond the end you figured

And is altered in fulfilment.

Alternatively, one could say that just like Marx is only now, 150 years later, in the midst of a financial crisis, coming into his own; postmodern thought, too, has yet to come into its own. 'Altermodern', on the other hand, in the world of Ideas may well be of the stillborn/undead variety.

Therefore in keeping with this fashion of inventing interesting buzzwords, I have come up with my own: AlterpostpunkAnarchoMarxistModernism. Whatever straw dummy Bourriaud in his out-of-touch world takes postmodernism to be may be 'dead', but this surely ain't. This, I claim, is the true 'sign of the times'; but alas, I haven't the time to elaborate on it here.

Sunday, 12 April 2009

Tamil protest; Picasso, repetition, and being-in-the-world

On my way to see the Picasso exhibition at the National Gallery yesterday (more on that below) I stumbled on the Tamil protest against the Sri Lankan government. As I was cycling down from Bloomsbury the car traffic was stalled for miles all the way up Charing Cross Road, at an almost complete standstill. Just as I was scanning the columns of cars weaving my way around lanes of traffic reciting my cyclist mantra - 'you fucking idiots, you fucking idiots, you fucking idiots...' - I reached Trafalgar square and noticed some commotion along the southern rim. At first it looked like there were a lot of English and British flags; and I thought this must be some BNP or UKIP follow-up to the G20 protests. As I got closer it became clear that something very different was afoot.

There were quite a few Tamil flags, but perhaps because there were so many, they were less conspicuous than the larger and more ominous Union Jacks and St George's crosses, which at first stood out against the sea of red and yellow.

There were men, women, young and old, children, even parents pushing prams...

The whole thing was pretty well orchestrated, with official march coordinators in bright yellow vests (not fluorescent, as that might offend the bobbies) reading 'FREE TAMIL EELAM' on the front and 'STOP Genocide of Tamils in Sri Lanka' on the back.

The Sri Lankan government has kept foreign journalists and aid workers out of the war zone, and made a comprehensive effort to ensure that, if the conflict is reported in foreign media at all, only its own side of the story is heard.

According to a Human Rights Watch report, the government has indiscriminately shelled civilian "no-fire" zones. Some investigators did get in, apparently. Read more about it in Arundhati Roy's piece for the Guardian.

Bobbies looking inconspicuous as always.

Back on Trafalgar Square, the current incarnation of the Fourth Plinth, Thomas Schütte's Model for a Hotel 2007 , a 5-m by 4.5 m by 5 m architectural model made of coloured glass. It was originally titled Hotel for the Birds (presumably before the artist got wind of Ken's ban on pigeons in the square).

I did eventually make it to the Picasso exhibition, which was also well organized.

Most refreshing and thought-stimulating were some of the perhaps less well-known or at least less clichéd works, such as the late variations on Velazquez, Monet, Van Gogh, and others.

'Imitation as the source of creativity' - it occurred to me - is only the art historian's clichéd sublimation of Deleuze's far more subversive proposition: that the truly new only ever emerges in repetition. Newness is by definition an effect of repetition, of return, of grasping an 'old' thing from a different angle: which is why only repetition produces the truly singular, and no two grains of sand are ever the 'same', cannot be reduced to the same thing - this one is this one and that one is that one - even if their molecular structure is identical.

Rather than being a return to the classical tradition (as suggested by some of the accompanying material), Picasso's explorations of his later years are only a more explicit way of stating what the underlying message was all along: neither a break with the past nor simply a continuation of it, but an incessant search for the new - the excess of innovation - through more and more radical forms of repetition.

It is not enough to say that if we do not know history, we are doomed to repeat it; or the inverse, 'you can't repeat the past'. Nor is it simply the opposite, the ancient wisdom of repetitio est mater studiorum. Each of these propositions falls short. Much more subversively, one must repeat in order not simply to learn but to transform and overcome the existing. One must repeat, in order to avoid replication: repetition is never repetition of the same. To repeat is always to repeat a problem, a possibility, a fork in the road. No wonder the most original artists and improvisers in any discipline are also the greatest imitators.

Some of Picasso's morbid imagery (cubist or otherwise) throws up a related problem: what Heidegger calls the 'hiddenness' of things. The cut-up and mix of objects and perspectives - the simultaneous presentation of profile and frontal views of faces, the back and front of a torso - is an index of the impossibility of seeing things in their completeness; not a 'cubist' or 'abstract' representation of reality but the marker of a representational void.

A part of things always remains hidden from view; and even the multiplication by a mirror remains only that - a multiplication of two-dimensional perspectives which never merge in a single perspective.

What makes these images morbid is their emphasis on the tension between a three-dimensional space and the impossibility not only of representing it, but of even seeing more than two dimensions; the suggestion being that the world would probably look very different, morbid even, in three dimensions. As Picasso himself put it, "Art is a lie that makes us realize the truth."

Sunday, 28 December 2008

The Straight Line and the Void: Hundertwasser, Hiroshima, and the Horror of Forgetting

Hundertwasser, the most important Viennese artist of the second half of the twentieth century, despised straight lines. Straight lines he thought immoral and atheistic. Painting is a religious experience. There are no straight lines in nature.

I have been photographing straight lines lately. They do seem mostly man-made, inasmuch as they can be called 'straight' - building cranes, jet streams, telephone cables, poles, railway tracks. But Hundertwasser is right - there are no straight lines in nature, even man-made. Everything is crooked, curved, bent, distorted, twisted - if you look close enough. Or inversely, if you stand back far enough. Straightness is a metaphor, or a mirage - and a dangerous one at that. A jet stream is nothing but a shapeless clutter of gusts, clouds, particles, hyperbolic streams.

"I venture to say that the line described by my feet as I go walking to the museum is more important than the lines one finds hanging on the walls inside. And I get enormous pleasure in seeing that the line is never straight, never confused, but it has its reasons for being the way it is in every smallest part. Beware of the straight line and the drunken line, but especially of the straight one! The straight line leads to the loss of humanity." (Hundertwasser, 27)

Hundertwasserhaus, a low-income apartment block in Vienna designed free of charge by the artist ("to prevent something ugly from going up in its place"), features undulating floors, an earth and grass-covered roof, and large trees growing inside rooms with limbs extending from windows. "An uneven floor is a melody to the feet," Hundertwasser was reported as saying.

Among the architectural features of the new Jewish Museum in Berlin designed by Daniel Libeskind is a Holocaust Void - "a void space that embodies absence, a straight line whose impenetrability becomes the central focus around which exhibitions are organized." (63) The straight line: the loss of humanity, the Holocaust.

In the novel We, a somewhat superior forerunner to Orwell's 1984, credited by Orwell himself as a major source of inspiration, Yevgeny Zamyatin writes: "Taming a wild zigzag along a tangent, toward the asymptote, into a straight line: yes. You see, the line of the One State - it is a straight line. A great, divine, precise, wise, straight line - the wisest of lines." (4) The straight line: totalitarian state.

"Everything straight lies," a dwarf tells Nietzsche's Zarathustra. "All truth is crooked, time itself is a circle." Even space is curved, as Relativity would have it.

According to the author of a book on the Sarajevo Hagaddah, the Nazis' aim in looting Jewish treasures from around the world was to house them in a "museum of an extinct people." All museums and galleries, to a greater or lesser extent, unwittingly or not, furnish this project: the past is another country. The gesture of putting on display a work objectifies and distances it; the work becomes the index of a complex absence, it opens up a space of alienation, a void. Every exhibition space is in a sense a 'museum of an extinct race'. It commemorates the absence of the artist, who no longer exists, who is extinct.

(*The inclusion of the Holocaust Void in the New Jewish Museum in Berlin, implying a negative content, could be a saving grace or counterweight to this tendency, by displacing the trauma of extermination not on a fixed positive content, but on a kind of vanishing mediator, fixing the gesture of petrification/alienation in a state of incompleteness, a straight line whose emptiness negates itself, and its 'straightness', opening up an empty space for thought and remembrance.)

Something to this effect happens to be the theme of an exhibition at Futura Gallery in Prague titled 'Key Figures in 20th Century Art'. It consists of a series of portraits of artists who, according to the authors of the project (Avdei Ter-Oganian and Vaclav Magid), have "contributed to the elimination of avant-garde tendencies" and given rise to the capitalist notion of the work of art as an object of consumption or 'commodity'. The logic of the commodity is inimical to the work of art, leading to what Ter-Oganian and Magid call an "ecological catastrophe in the cultural sphere". The artists whose portraits are hung on the 'wall of shame', ranging from Gustav Klimt to Tracey Emin, have "left the world of art and sold themselves to the production of worthless yet luxury commodities." The artists have vacated their own bodies.

A series of works by photographer Susan Hiller titled 'The J Street Project', accompanied by a lengthy printed volume, documents 303 German streets that contain the word 'Jude' - 'Jew'. Hiller's research resulted in over 300 photographs, a list of places and streets with a map of Germany, and a video installation. Given the perverse logic of the Nazis' collecting habits, however, the persistence of the street names that Hiller documents is not at odds with the 'traumatic absence' they indicate. Street names are like museums and galleries, for the most part - they are not there to help us remember, but to help us forget. They obliterate the past in its immediacy, sublimate the horror - the 'past present' - in a petrified image, an always-was.

Forgetting is the recurring theme in all this - in the film Hiroshima mon Amour, the phrase 'horror of forgetting' appears. No longer the horror of the event itself - of the bomb, of torture, of the loss of love - but horror at the loss of memory of the horror. Horror when confronted with the possibility that such intense love or suffering can fade in spite of all efforts to the contrary, that one can eventually go on living 'as if nothing ever happened'. That objects lose their signifying power. That the meaning of a sign can be reversed.

It is in this that the horror of intense love and intense suffering are one. "Just as in love this illusion exists, this illusion of being able never to forget, so I was under the illusion that I would never forget Hiroshima." (212) The woman from Nevers is constituted by the horror she suffers; she preserves her identity by preserving the memory of lost love, its intensity. Underneath, the true horror - the horror that there is no horror, that the animal survives, that no pain, torture, death, or love can kill it. This is the truly horrifying thing - the animal in us that overcomes the horror. The remainder, the muselmann of Auschwitz, the straight line that perseveres. Vertigo, as Kundera put it, is not the fear of falling, but the fear of our own longing to fall.

One of the pitfalls to any resistance struggle, as Michel Foucault warns, is attachment to an identity of subject instituted or coagulated in a situation of oppression, the constitution of an identity permanently marked and defined by subjugation. By taking one's own victimization permanently for granted one easily forgets its objective moral imperatives, ignoring one's own capacity to do evil, freeing one's conscience to subject others, to become the very thing one struggled against, in another struggle. (As Israel's treatment of Palestinians shows, most recently in the attacks on Gaza the past week...) True resistance must lie somewhere inbetween - between the horror of forgetting and total oblivion. It must entail a real, mobile multiculturalism - hybrid, rhizomatic, chameleonic - rather than the liberal pandering to the Other as other, which fixes the Other permanently in a state of subjugation and/or permanently assigns to it a positive content. A transcendental multiculturalism whose horizon of possibility includes not mere understanding of but being the Other through/as oneself, recognizing one's own experience in the experience of the Other.

The Nazis never managed to get their hands on the Sarajevo Haggadah on account of a clever ruse by a Muslim librarian and Islamic scholar named Dervis Korkut. When a German officer came to collect the book at the National Museum in Sarajevo, the museum curator informed him that another SS officer had just collected it and left. The straight-thinking German took the bait and left, frustrated. Korkut left by the back door, Haggadah in hand.

Korkut took the book to his home village, and hid it in the home of a Muslim family (or in a mosque, according to another version of the story), mixed in with Islamic texts. As the Germans assumed all Muslims were collaborators (on account of the simple dichotomy of Muslim/Jew), they were not in the habit of searching Muslim homes. Like Poe's purloined letter, the Sarajevo Haggadah becomes a Deleuzian virtual object, by definition displaced - it is what it is by virtue of never being where it is expected. It eludes the grasp of its pursuers because it is by definition a Jewish book rescued by a Muslim librarian.

The Haggadah survived the most recent Bosnian war and the burning of the National Library in Sarajevo by Serb artillery. It was again rescued by a Muslim, a museum curator this time. It lives, invisibly. The asymptote, the zigzag, the wandering path of an ancient book defeats the straight line of the howitzer barrel.

*

* * *

Restany, Hundertwasser (2008)

Saltzman & Rosenberg (ed), Trauma and Visuality in Modernity (2006)

Wolf, Daniel Libeskind and the Contemporary Jewish Museum (2008)

Zamyatin, We (2006)

New York Times article on Hitler's plans for a 'museum of an extinct race'.

New Yorker essay on Sarajevo Haggadah