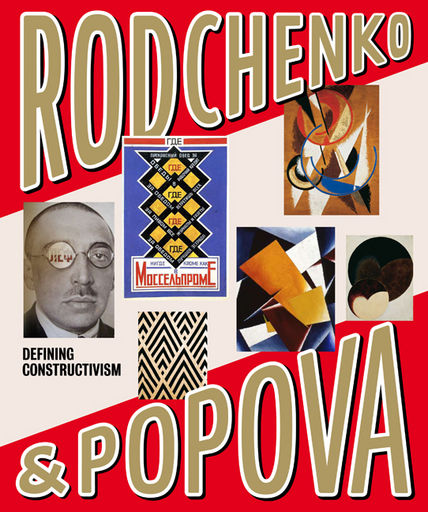

Far more refreshing than the 'Altermodern' Triennial at the Tate Britain, the special exhibition at the Tate Modern, 'Rodchenko and Popova' provides a comprehensive but by no means nauseating retrospective on the art of the revolution, as it flourished before the thermidor of Socialist Realism. If any 20th century art movement should be revived and rethought, I say, it should be Russian Constructivism.

In fact if, as Zizek says, the future will be either socialist or communist - 'socialist' meaning the kind of nanny-state capitalism practised by Western governments in the wake of the financial crisis - for the art world this must mean that the future will be either Altermodern or Constructivist. Art will either remain more or less what it is, a distinct sphere of rationality backed up by specific forms of cultural practices and modes of communication, or it will be sublated in a multidisiplinary network within an overall revolutionary dissolution of separate social spheres and disciplines.

'Altermodern' is clearly the tendency to be opposed, but not so much for the content of the art it takes under its wing - a lot of which, as discussed earlier, can be described as 'postmodern', in spite of its curator Nicolas Bourriaud's proclamation that 'postmodernism is dead' (kind of like Leonard Cohen's lyric... "I fought against the bottle/but I had to do it drunk..."). What should be opposed is not the art but the critical tendency - the mentality of 'out with the old, in with the new' - exemplified in equal measure by buzzwords like 'Altermodern' and by the spectre of Wall Street's return to Marx. ('retro' is now the 'in' thing...)

The issue is not that these are mere 'surface effects' but precisely that they exhibit the opposite or inverse tendency of 'depth without breath', of getting to the bottom of a problem but only after the fact, only when the damage is already done. Why did we need a complete breakdown of the system in order to correct its course, if it is at all a correction? (I personally don't find the idea of bankers reading Das Kapital very convincing.) Or why did we need a total degeneration of the art world into a commercial meat market in order for someone to suggest something is wrong?

What is needed is not merely a new form of art - let alone a new buzzword, a new name, a new way forward or into the depths - but a new way of thinking about the very production process of art and its social function, something which the constructivists, unlike most art movements, sought to do. What is needed is precisely not more depth, nor a different kind of depth, but more breadth: the extension of art into other realms. Let's face it: to what extent does Bourriaud's theorizing really exhibit the traces of a 'universal language'? Isn't the work of "translation" at stake in this 'altermodern' phenomenon merely the transcription of a myriad of untranslatable cultural phenomena into one non-universal and even somewhat esoteric language particular to the foofy contemporary art circuit, and largely unintelligible to the majority of society globally?

The language of lines and forms, on the other hand, is a universal language - if for no other reason than what one could call its 'primitivism'.

Constructivist design for a cup and saucer

But even more so, an art that rejects the notion of "art for art's' sake", an art that believes art must be put to use - in addition to the promise of social change built into its very core and fibre, must speak a universal language in order to exist. It can only exist on condition of extending its breadth, of its expansion into 'non-art'.

At the same time, the constructivist egalitarian rejection of the term 'artist' in favour of 'constructor', the simplification of the process of creation, to demistify art, etc - hints at the postmodern 'death of the author'; in both cases the aim is to undermine the privileged position of the speaker/author/artist as the arbiter of meaning or aesthetic value in favour of a configuration where the very dichotomy of author/consumer becomes false. Art for the people.

In this context the reference to 'modern' in 'altermodern', and the call "death to postmodernism" can be read as the thermidorian gesture of restoring order, repeating Stalin's gesture of outlawing constructivism and proclaiming Socialist Realism as the only acceptable form of art.

Constructivist clothing design: clearly the future

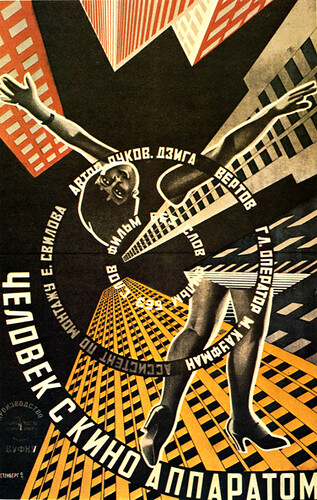

Another thing worth thinking about is the constructivists' involvement in advertising, and their insistence on not rejecting it as a capitalist consumerist ploy. There is something to this: for how can one confront the phenomenon of advertising at all, if not with advertising itself - either in the form of subversive re-production (i.e. Adbusters) or in the form of counter-advertising, advertising for the right causes?

The Adbusters slogan for what they have dubbed 'Buy Nothing day', November 22, has a distinctly constructivist ring: MAKE SOMETHING - BUY NOTHING.

From now on, I am no longer the author of this blog, but its chief constructor.

Monday, 20 April 2009

Constructivism and the Future

Wednesday, 15 April 2009

Punkstmodernism is not dead: notes from behind the irony curtain

I hate it when people declare something 'dead' when it's actually not.

Scratch that. I hate it when people say that an Idea is dead, period. Sure, there are dead ideas; but that's because they never were real Ideas, because they were born dead. Just like "manuscripts don't burn" - Ideas don't die. In the world of Ideas, the only things that can ever legitimately be declared 'dead' are those that never were - the many false starts, misapprehensions, misdirections in the history of human thought. Ideas do not oscillate between the living and the dead; they oscillate between the living and the stillborn. Confusion slips in when the latter go on 'living', Zombie-like, 'undead' - until centuries later some rare, clear-sighted specimen of our blundering race sees through the folly, and tells it like it is.

Sadly enough, Nicolas Bourriaud - art critic, curator, and co-founder of the Palais de Tokyo - is no such gent, and he doesn't tell it like it is. Postmodernism is not dead. It is alive and kicking, and there is nothing radically new here. Postmodernism, like every great idea, has been declared dead before - most notably after September 11, when neoliberal apparatchiks excitedly whispered that the 'age of irony' was over. In fact, Derrida's strain was even declared 'dead on arrival', years ago, before the term 'deconstruction' embedded itself in the vocabulary of art and philosophy to the point of becoming a cliche.

The thing about irony is that - like dialectics - it just never goes away. It's worse than cancer. The more you 'excise' it, the more it multiplies - the more ironic the irony gets.

When people do declare an idea to be dead, this does signal a change, but it is often not the change they are counting on - it is very often the contrary. Just when Francis Fukuyama announced the 'end of history' in the Final Age of liberal democracy, he himself soon withdrew the proclamation. Just when it looked like Global Capitalism was going to be the only game in town for good after the fabled 'fall of communism' in the 90s and the various proclamations that the 'age of ideologies' was over, the financial system collapsed and people started reading Marx again.

And just as Nicolas Bourriaud proclaimed that 'postmodernism is dead', postmodernism reared its little head all over the very exhibition that Bourriaud curated this Spring at Tate Britain to signal the death of postmodernism and the birth of what he has dubbed 'altermodern'. Isn't that, like, ironic?

I did like some of the works I saw, but I didn't find the show as a whole especially refreshing as against the contemporary art scene today. But rather than comment on the merits here, I will only address a few examples in relation to ('postmodern') theory. All quotations addressing the works and artists in the Triennial are from the exhibition guide.

Tacita Dean's work 'The Russian Ending' 2001, one of the highlights of the exhibition, is inspired by an early twentieth century custom in the Danish film industry where each film was produced in two versions: a happy one for the American market, and an alternative with a depressing or tragic ending for the Russian market. Taking images of disasters from original postcards purchased in flea markets, Dean uses handwritten notes that suggest the storyboard of a film to provide "imagined endings to imagined films."

What Dean is clearly getting at is the ambiguity of meaning in text and narrative that this reference to the Danish film tradition evokes; she inserts, for instance, coy double entendres such as 'man's laughter/manslaughter' - play, irony, reversal of signs. How is this in any sense not postmodern? Decontextualizing/recontextualizing images to imbue them with a meaning unimagined by their authors, through writing - palimpsest - and moreover suggesting "imagined endings to imagined films", is this not post-modernism par excellence? A perfect example of - whatchamacallit - deconstruction?

Similarly, Peter Coffin's work 'Untitled (Tate Britain)' 2009, projects animations with soundtracks onto existing artworks from the Tate's collection. The works "remain both in their conventional habitat and simultaneously become mobilised as fictitious characters in a new narrative scenario which...opens up a web of associations." In this way, Coffin "charges existing artworks with a life and mind of their own."

Oh, you mean that whole thing about the "death of the author" - how the 'meaning' of a work/text/utterance does not reside simply in the mind of the original speaker/author? Yep, nothing new there. Derrida again, right? And a bit of Barthes?

Rachel Harrison "splices together found objects, images, and hand-sculpted abstract forms to create installations that possess the iconoclastic energy of Punk...presents all her material on an equal footing and wilfully flattens out any cultural hierarchies." If that doesn't sound 'postmodern' enough, her work in the exhibition, 'Voyage of the Beagle, 2007', a "pantheon of fifty-eight portraits of figures and sculptures, from ancient artefacts to shop mannequins" - including a pelican, a buddha statue, a bear, an Elvis mannekin, a bear, a superman blow-up doll, all shot and framed identically and hung in a series - "functions as a sort of anti-taxonomy, mocking ideas of progression or systems of classification and otherness."

This anti-taxonomy is what Michel Foucault would refer to as a 'heterotopia' - an impossible place where all the unclassifiable junk is secluded in order to make a 'utopia' of order and reason (and taxonomy) 'possible'. Except that in The Order of Things - a work emblematic of precisely Foucault-the-poststructuralist - he goes even further. Harrison's work is just not radical or probing enough. A major inspiration for Foucault, cited in the famous introduction, was a short story by Jorge Luis Borges - a 'modern' writer (more on that below) - in which he mentions a "certain Chinese encyclopedia" which divides animals into

"(a) those that belong to the emperor; (b) embalmed ones; (c) those that are trained; (d) suckling pigs; (e) mermaids; (f) fabulous ones; (g) stray dogs; (h) those that are included in this classification; (i) those that tremble as if they were mad; (j) innumerable ones; (k) those drawn with a very fine camel's-hair brush; (l) etcetera; (m) those that have just broken the flower vase; (n) those that at a distance resemble flies."

This passage, to Foucault

"shattered thought...breaking up all the ordered surfaces and all the planes with which we are accustomed to tame the wild profusion of existing things...to disturb and threaten with collapse our age-old distinction between the Same and the Other...Moreover, it is not simply the oddity of unusual juxtapositions that we are faced with here...like the umbrella and the sewing machine on the operating table. The monstrous quality that runs through Borges's enumeration consists, on the contrary, in the fact that the common ground on which such meetings are possible has itself been destroyed...A vanishing trick that is masked or, rather, laughably indicated by our alphabetical order...What has been removed, in short, is the famous 'operating table'."

Another work, Simon Starling's 'Three White Desks', is made up of three copies of a no longer existing desk designed by Francis Bacon for Australian writer Patrick White. Only the first desk is a copy of it in fact, made by a cabinet maker after the only surviving photo. The second one, made after an identical photo of the first desk, is a copy of a copy, and is in turn photographed...you get the picture. The third desk is a "copy of a copy of a copy."

The disavowed reference is clear - Warhol only did it better, with more umph. The added dimension in Starling's 'altermodern' approach is having each copy made by a different cabinet-maker in a different country, each in a city relevant to the story of the original desk. But this unnecessary step, which makes for an 'interesting story', only obscures the key point - that repetition alone produces change, without any added input. If one artist alone makes copies of a thing, by the same method, in the same medium - after a sufficient number of repetitions the copy becomes a simulacrum. Each repetition brings about a change, however minuscule. This work, then, tells us nothing significant about 'cultural exchange' and 'translation' between cultural milieus or mediums - every copy, every repetition is a 'translation', every work - every copy in fact - a 'cultural milieu' unto itself on a microcosmic scale.

Here's Deleuze, one of the, you know, key dudes of postructuralist/postmodern philosophy, writing about Warhol circa 1968, p 366, Difference and Repetition [my italics]:

"Each art has its interrelated techniques or repetitions, the critical and revolutionary power of which may attain the highest degree and lead us from the sad repetitions of habit to the profound repetitions of memory, and then to the ultimate repetitions of death in which our freedom is played out...the manner in which, within painting, Pop Art pushed the copy, copy of the copy, etc., to that extreme point at which it reverses and becomes a simulacrum (such as Warhol's remarkable "serial" series, in which all the repetitions of habit, memory and death are conjugated)..."

I rest my case.

Reading Bourriaud's introductory text I find myself baffled - it oscillates between totally meaningless commercial art-world jargon with no apparent relationship to most of the works in the exhibition, other than what could be said of any contemporary art ("the figure of the artist as homo viator, a traveller whose passage through signs and formats reflects a contemporary experience of mobility"); and a schoolboy's highly simplified rendition of precisely postmodern philosophy, i.e. Deleuze - "lines drawn both in space and time, materializing trajectories rather than destinations, expressing a course or a wandering rather than a fixed space-time"; the term 'altermodern', he tells us, "suggests a multitude of possibilities, of alternatives to a single route."

Très chic. Yet this somehow means that the "historical period defined by postmodernism is coming to an end"? Not with these kinds of contradictions to play with.

Derrida can be read into this discussion as a kind of arch-Marxist: where Marx saw internal contradictions in capitalism, Derrida saw internal contradictions everywhere. Deconstruction is internal to things - and this is what bugs me when people throw these words around without grasping them, and write stuff like 'Artist so-and-so uses conceptual approaches to such-and-such to deconstruct notions of this-and-that with reference to narratives of something-or-other', and so forth. People don't deconstruct anything - deconstruction is a passive process, a force of nature. It can only be shown - one can only draw attention to the self-deconstruction of, say, a text. Things deconstruct themselves, break down into their constituent components, expose their own contradictions, generate their own opposites and internal differences. Language deconstructs itself through repetition. Ideas deconstruct themselves. Modernity, too, deconstructs itself; and Bourriaud's 'Altermodern' triennial is a case in point.

'Altermodern' decomposes, ironically enough, into a poor copy of 'postmodern'. And by 'poor' I don't mean artistic merit or 'faithfulness to original', but quite the contrary - poor in the sense that it falls short of its own mark, that within a history of thought, it doesn't represent a development in the way in which 'postmodernity' was a development of 'modernity'.

One of the great lessons of one of the key philosophers of modernity, Hegel, was this: something that appears to be refuted - annihilated - in the progression of thought, is merely sublated. (Aufhebung) One of Hegel's favourite metaphors was that of a flower springing from a bud, appearing to destroy the bud in the process; the flower blooms, the bud disappears. Nevertheless, without the bud there would be no flower - it is the bud that gives birth to the flower, and remains sublated within it.

Postmodernity is a moment in the history of thought - one of its key realizations as against modernity being that meaning and language are inherently unstable; that identity is unstable; that concepts themselves are unstable and their meanings shift, evolve. Even terms like 'modern' and 'postmodern' or 'poststructuralist' are themselves inherently unstable, and were rarely - if ever - self-applied by those thinkers usually corralled under them by high-minded critics concerned with fads and fashionable phrases.

We cannot simply retreat from that, abandon that moment in thought, pretend it didn't happen. In Deleuze, the dialectic exemplified in Hegel's metaphor translates into becoming. But becoming - what Bourriaud might call "trajectories rather than destinations" - encompasses more than Hegel's dialectic because Deleuze, among other things, had Darwin and evolutionary science behind him. Becoming takes account not only of a process of growth in the sense of a single living organism (even as a microcosm of world spirit), but the whole process of genetic development and actualization, which adds complexities - is more in the vein of 'rhizomatic'. It can move and split in any direction and does not follow any clear, determinable path to 'Progress' but only adaptation, neither up nor down, neither forward nor back; and it is dependent precisely on processes of repetition - the copy of a copy of a copy, etc - which over time generate the truly new in nature.

To Deleuze, the very suggestion that there is an opposition (real or apparent) between 'bud' and 'flower' as distinct identities, and that one annihilates or even appears to annihilate the other, would be false: this is the field of the negative, the 'false problem' or 'the fetish in person'. The one, rather, becomes the other, morphs into it. Together they form a 'trajectory' rather than two 'destinations' or 'points'.

In this vein, I find Bourriaud's notion of 'altermodern', at least from what I have so far seen in practice, very un-becoming.

Altermodernity hasn't come up with any truly new problems in relation to postmodernity. To use Bourriaud's own terminology, what he has missed is that the relation modern-postmodern is precisely that - a relation, in which neither is a fixed point in space/time - the two form a trajectory in which neither can be reduced to simply itself, or disengaged from the other.

Ideas - real ideas, generating real problems - don't die; and many of the pieces in the 'altermodern' exhibition demonstrate that the Idea in question here - the 'postmodern' one - is very much a real Idea, embodied in actual objects, even ones whose authors or curators claim that that same idea is 'dead'. Irony is indeed alive and well.

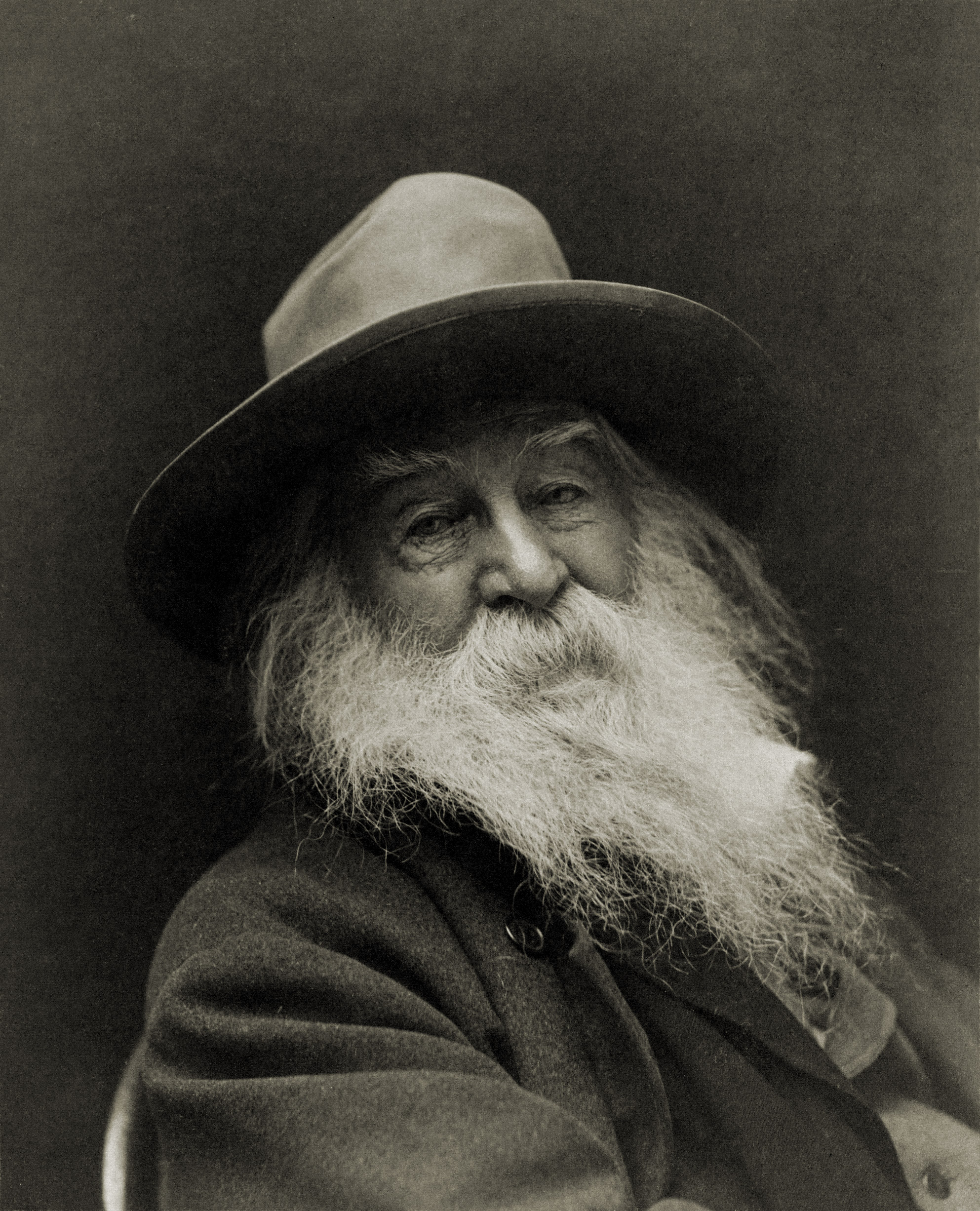

The thing is, writers and poets always 'got it' before art critics and historians did. Rimbaud's famous remark in a letter to a friend - Je est un autre ('I is another') - has long been mulled over as a herald of postmodernity. Jack Kerouac's "it ain't whatcha write, but the way 'atcha write it" hints at the notion of différance. Yet another great poet once wrote

Do I contradict myself? Very well then

I contradict myself.

I am large, I contain multitudes.

Now that sounds pretty damn post-modern to me. When was it written? 1855. Walt Whitman.

In the case of some writers, who stand in the margins and evade easy pinning down, such as the Portuguese Fernando Pessoa, people have debates and ask: was s/he modern or postmodern? And I say to that: does it matter? Only the Ideas matter in the end. Where 'modern' stops and 'postmodern' begins is a matter of pointless pedantry.

Walt Whitman - clearly postmodern

These writers - Foucault included - themselves embody that trajectory in thought, the discovery - the transition from 'modern' to 'postmodern'.

I am tempted to speculate here that Bourriaud may in fact have a point, however not the one he figures - that perhaps the rise of fads and buzzwords like 'altermodern' in today's global financial capitalist world does signal a new era, but one which is still postmodern, even ultrapostmodern rather than 'altermodern'. What we may be faced with here is a stripped-down version, a 'bare repetition' of postmodernity without self-awareness, or with a kind of false consciousness - a thoroughly unhinged postmodernity unaware of its own historical moorings, under a different name, a different guise. An even more postmodern postmodernity, precisely because it doesn't call itself that. (very much in line with Zizek's remark that one of the dangers of today's global capitalism is that it 'no longer calls itself capitalism.') Postmodernity, in other words, is Altermodernity's unnameable core - its Big Other - the elephant in the room.

So, there - deconstruct that.

As another modernist poet - whose words also have a distinctly post-modern/Taoist ring at times - T.S. Eliot, put it:

Is only a shell, a husk of meaning

From which the purpose breaks only when it is fulfilled

If at all. Either you had no purpose

Or the purpose is beyond the end you figured

And is altered in fulfilment.

Alternatively, one could say that just like Marx is only now, 150 years later, in the midst of a financial crisis, coming into his own; postmodern thought, too, has yet to come into its own. 'Altermodern', on the other hand, in the world of Ideas may well be of the stillborn/undead variety.

Therefore in keeping with this fashion of inventing interesting buzzwords, I have come up with my own: AlterpostpunkAnarchoMarxistModernism. Whatever straw dummy Bourriaud in his out-of-touch world takes postmodernism to be may be 'dead', but this surely ain't. This, I claim, is the true 'sign of the times'; but alas, I haven't the time to elaborate on it here.

Monday, 13 April 2009

Tamil sit-in at Parliament Square and the Bug of Colonial Cynicism

It seems every time I go see an exhibition the past few days, I run into a Tamil protest. This time it was the Altermodern triennial at Tate Britain (of which I will write more later), and my Tamil friends were staging a sit-in at Parliament Square. I shot some more photos, but concentrated mostly on video footage this time, which I have edited into a short film, posted above through Youtube. (I shot in high-definition, but unfortunately it has gone through various conversions for upload...hm. something to work on. I am quite fond of the last shot, with the Churchill statue looming over the crowd as the clock of Westminster Cathedral stikes seven.)

These protests have been going on for several days and have blocked streets in central London, the one on Saturday drawing a crowd of 100,000 according to official police figures; yet it has hardly made the headlines. (Partly explainable by the Sri Lankan government's ban on foreign journalists.)

One key thing to note is that although Tamil communities worldwide have been staging protests and sit-ins, there is an added significance here. Unsurprisingly, the root of the conflict in Sri Lanka is one of many British colonial leftovers - the creation by Crown mandate, on the departure of the British from Sri Lanka (formerly known as Ceylon), of an artificial statelet - without regard to pre-existing regional demographic differences and related claims to autonomy, in this case the Tamil minority who were left in a repressive majority-Sinhalese statelet.

I am tempted to come up with a jibe here on the likelihood that all this had something to do with preserving the supply - and of course the impeccable flavour - of English tea.

It also strikes me that almost any existing armed conflict in the world today, now, that I can think of is rooted in some mess left by European colonialists - usually British - upon their departure; and in almost every single case, the root cause is a cynical disregard of demographic, political, and ethnic differences in carving out artificial statelets, power usually being doled out to the most loyal or cooperative of colonial subjects. Palestine, Pakistan, Iraq, Iran, Afghanistan, East Timor, Somalia, Ethiopia, you name it - case after case, the map of armed conflict in the world today is almost invariably a series of variations on a theme.

Just look at a map of Africa - look at all those perfectly straight lines. I mean, sure, desert and savanna is pretty straightforward territory if you're drawing borders. But who drew them? Do you think they largely reflect the migratory patterns of Bedouin tribes, or the whims of colonial prelates of yore?

And then they blame the mess in the world on the genetic proclivity of 'darker races' to engage in violence. (I have personally witnessed a member of the liberal British upper classes - a Guardian-reading, public school-educated PhD student in urban development at UCL - quietly elaborate this point to me once on a bus chock-full of local immigrants in Dalston, in relation both to the causes of the high crime rate in Hackney and the violence in the world in general; it was one of my first cultural shocks in Britain, and I shall never forget my initial disbelief that he was indeed suggesting - indeed, in a very British, understated manner - what I was indeed hearing...)

To be fair, the British certainly aren't the only ones to blame, and one should also take into account places like Vietnam and Korea - the product of a similar colonial bug, albeit of a more modern, Soviet-American-Franco-Chinese variety. (interestingly enough, both countries were split between a communist north and a pro-Western south, in both cases reflecting no known actual demographic divisions, but rather the balance of power between the occupying forces.)

And yet it seems to me that almost all the key hotspots brewing right now - Palestine, Iraq, Sri Lanka - can be traced back to British colonial rule. Sure, it's complicated. Sure, there is a situation on the ground and there is no simple solution - not anymore at least. But is it just that the British are unlucky, and happened to take on the most difficult places with the most complicated histories under their domain, or is it that there is something particularly cynical about their methods of colonial government? An example much closer to home - Ireland - might be instructive, since it poses similar dilemmas and complications.

The British government's way of washing its hands clean of the mess in Sri Lanka at present is to dismiss the Tamil Tigers, as other governments have, following Sri Lanka's cue, as a terrorist organization. The best indication of the cynicism of such policies, in light of what is known about the conflict, is the double standard applied by the USA and other governments to the kurds, as documented in the film Good Kurds, Bad Kurds : the Iraqi Kurds, who are useful, are treated as 'freedom fighters'; the Turkish Kurds, who are essentially part of the same movement, have the same goals and deploy the same methods, are 'terrorists', because Turkey is an ally.

It is for this reason that the Tamil protesters' slogans include 'Tigers are our freedom fighters'.

In light of all this, it is commendable that they still wave the British flag at their protests, instead of burning it, as I surely would in their shoes.

Sunday, 12 April 2009

G20 and the rise of disciplinary power: the bankruptcy of justice

The Guardian has posted stories of mistreatment of civilians by police during the G20 protest, along with a version of the video (above) showing the police assault Ian Tomlinson, who later suffered a heart attack, as he was making his way home. The Guardian edit of the original video (the first one to surface, shot by a bystander) includes a slow-motion replay and action highlights.

This, along with the thousands of other such stories that go unreported with every protest because they do not result in deaths (take the use of harassment legislation to curb protests, discussed in an earlier post), is a good index of the rise of disciplinary power in contemporary Western society.

The fact that no major riots or anti-police actions have broken out is a measure of the effectiveness of that power, even when it exceeds its bounds. (Think of the Rodney King riots in LA) An individual officer may get reprimanded; but the overall effect is a success, the message hit home. Just as the rhetoric of freedom and democratic values in the age of the 'war on terror' and the 'clash of civilizations' has heated up, the police on this side of the fence are getting more brutal. (Incidentally, an item in the Readings section of this month's issue of Harper's details a lawsuit filed by the family of a 12-year-old black girl in Texas who in 2006 was brutally beaten by police officers on her parents' lawn for resisting arrest on charges of being a prostitute. The family "eventually learned that the dispatch call the officers were responding to reported three white female prostitutes soliciting men half a block from the family’s home.")![]()

This split in Power theorized by Foucault - between the conventional form it takes in the West in the sovereign legal right, and its modern form in disciplinary power, is perhaps more real than ever. Even when police actions are questioned, they are not questioned on the basis of right, but on the logic of necessity - i.e. was it reasonable under the circumstances, were security measures that led to this shooting or that beating necessary in view of the threats, etc (who gets to measure such things?).

Even when rights are infringed (think of the De Menezes shooting), this is irrelevant so long as the measures taken are deemed to have been necessary, and the innocent casualty becomes simply the victim of an 'unfortunate accident'. Rights only come into play to cover up the bare bones of disiplinary mechanics.

In other words, disciplinary power is questioned only on its own terms, on the logic of necessity. The only question that can be asked of it is: 'is it necessary to take such measures in order to produce the desired effects/goals?' One is not allowed to question the effects/goals themselves, or their justification. One is not allowed to suggest that a particular measure is illegitimate because it may or is bound to infringe on a particular political/natural/legal right.

Yet it is clear that the real 'necessity' behind the techniques of discipline is not security from terrorism or from particular threats - this can never be achieved one hundred percent as proto-fascist security barons would believe - but the disciplining of the population, the deployment of techniques of discipline and 'normalization' without popular or democratic oversight. It is no surprise that the recent crackdown on supposed Pakistani terrorists using student visas came on the heels of the police brutality at the G20 protest - the timing was no doubt arranged to downplay police brutality and conflate the threat of 'terror' with the threat of the protesters - something which New Labour politicians have attempted to do explicitly, making statements that liken anti-globalization protesters to Bin Laden, etc. It was just oh-so-convenient that Bob Quick misplaced a memo and they had to crack down early.

With each new crackdown and ensuing security measures, i.e. no bottled water, taking off one's shoes at airports, one lighter per passenger (what is it that can be done with one but not with two?) - the 'terrorists' try something else because, of course, they won't try bottled liquid explosives or shoe explosives again; and the possibilities are endless when one is willing to give one's own life up in the process. Yet the retrospectively enacted measures stay in place, however useless they are in the long run, after the fact; because their ultimate target is the population at large; and their aim is teaching discipline and obedience to authority, regulating and corralling the mass of ordinary citizens, teaching them to execute commands without asking questions. We're all in the army now.

No doubt there will soon be new restrictions on student visas and entry clearances, allegedly for security but in reality with a view to organizing a 'reasonable racism' or 'reasonable xenophobia', to borrow a formulation used by Slavoj Zizek in recent lectures.

It is notable that in the torture debate of recent years, even those liberals who maintained their principled opposition to torture for the most part found it necessary to assert that anyway, the intelligence obtained by torture is unreliable, that people will say anything you want them to under torture. It is insufficient, in other words, to assert that torture is unethical, that 'we are becoming like them', that it infringes the legal or natural rights of suspects, etc. One must always also engage the technical point; one must question disciplinary power on its own terms, on the issue of necessity and efficiency.

And the power of disciplinary mechanics is ultimately the only real power, or as Foucault put it, the 'mode in which power is actually exercised...power at the point of its application to bodies' ; as opposed to vague or abstract notions of sovereignty and autonomy and democracy and legal right. Disciplinary power constrains and subordinates any recourse to legal action or legal right, rather than being constrained by it.

It is this same power that is at the bottom of the financial meltdown and the ongoing recession, in the form of economic disciplinary power. The goal of neoliberal economics from Milton Friedman onwards has been nothing less than to wrest economics from the domain of political sovereignty and right, and bring it fully within the scope of discipline, within disciplinary power. Disciplinary power, as Foucault shows in his analyses of various social domains (prisons, hospitals, schools, etc) is constituted by what he calls the 'medicalization' of knowledge: this is where the notion of economic 'shock therapy' fits in neatly - a term that Naomi Klein in her critique of neoliberal economics did not coin but borrowed from Milton Friedman, the neoliberal shock doctor in person. (at a time when, of course, 'shock therapy' was still believed to be valid medical science; nonetheless, it is a good example of self-incriminating statements, however unwittingly made)

And it is through the 'medicalization' - one could say de-politicization - of economic knowledge that the neoliberal 'shock doctors' were able to take key economic decisions regarding deregulation of markets and other economic reforms outside the political and democratic sphere, and into the scientific/technical sphere. There is no room in the edifices of modern government to question economic policy, because economic policy has become a matter of science, of mechanical necessity, of technical knowledge - not political decision. We are meant to take it on faith that state assets, utilities, schools, prisons and the like must be privatized or turn to private sources of funding, that taxes must be lowered, that credit interest rates must be set to suit the banks, that there just isn't enough money to cover the cost of social security and other benefits even as taxes are being lowered for the benefit of the super-rich or when - even during a once-in-a-century recession - billions are given away in a massive 'benefits package' to banks, and so forth. What should be political decisions take the form of unconditional demands, mechanical necessities.

The only good answer to this is to say, as Martin Luther King did in the march on Washington, that "we refuse to believe that the Bank of Justice is bankrupt." We must cash our cheque. Our demands too must be unconditional.

This is a point where it is no longer even that the ends justify the means - in the Machiavellian schema one still has to justify the ends, promote a 'just' end. In the sinister logic of neoliberal capitalism, the ends are taken to be self-evidently just and fully identified with the means chosen. The relation between ends and means cannot be questioned, since it is the mechanical result of 'economic science'.

Two articles also in this month's issue of Harper's provide the most incisive critique I have yet seen of the current economic crisis and its roots in several key moments of deregulation of the US economy over the past several decades - in particular, the deregulation of interest rates and wages.

INFINITE DEBT: How unlimited interest rates destroyed the economy details how the elimination of the right to form unions in key sectors of the economy and the subsequent union-busting led to an effective pay freeze - no real increase in the minimum or average wages over 40 years, even as the economy grew - driving millions of people into levels of debt unfathomable to their parents; this, coupled with the constitutional legalization of usury - i.e. unlimited credit card interest rates - promising supernormal profit margins, drove all the capital out of manufacturing (a strong union sector but with lower profit margins) into banking and finance, lining up the key elements to ignite the crisis. This is what ensured the decline of Detroit and the rise of Wall Street since the mid-1980s.

Usury country: Welcome to the birthplace of payday lending is a more documentary account of an industry that, with its beginnings in the state of Tennessee, has effectively come into being as an industry and exploded across the USA since the early 1990s. Payday lending - as in dodgy businesses that lend people an advance on their monthly salary at six-figure annual interest rates when they can't pay the bills (no kidding) is rightly referred to by the author as a modern-day form of sharecropping. Or in Foucauldian terminology, another one of those techniques of disciplinary mechanics.

Tamil protest; Picasso, repetition, and being-in-the-world

On my way to see the Picasso exhibition at the National Gallery yesterday (more on that below) I stumbled on the Tamil protest against the Sri Lankan government. As I was cycling down from Bloomsbury the car traffic was stalled for miles all the way up Charing Cross Road, at an almost complete standstill. Just as I was scanning the columns of cars weaving my way around lanes of traffic reciting my cyclist mantra - 'you fucking idiots, you fucking idiots, you fucking idiots...' - I reached Trafalgar square and noticed some commotion along the southern rim. At first it looked like there were a lot of English and British flags; and I thought this must be some BNP or UKIP follow-up to the G20 protests. As I got closer it became clear that something very different was afoot.

There were quite a few Tamil flags, but perhaps because there were so many, they were less conspicuous than the larger and more ominous Union Jacks and St George's crosses, which at first stood out against the sea of red and yellow.

There were men, women, young and old, children, even parents pushing prams...

The whole thing was pretty well orchestrated, with official march coordinators in bright yellow vests (not fluorescent, as that might offend the bobbies) reading 'FREE TAMIL EELAM' on the front and 'STOP Genocide of Tamils in Sri Lanka' on the back.

The Sri Lankan government has kept foreign journalists and aid workers out of the war zone, and made a comprehensive effort to ensure that, if the conflict is reported in foreign media at all, only its own side of the story is heard.

According to a Human Rights Watch report, the government has indiscriminately shelled civilian "no-fire" zones. Some investigators did get in, apparently. Read more about it in Arundhati Roy's piece for the Guardian.

Bobbies looking inconspicuous as always.

Back on Trafalgar Square, the current incarnation of the Fourth Plinth, Thomas Schütte's Model for a Hotel 2007 , a 5-m by 4.5 m by 5 m architectural model made of coloured glass. It was originally titled Hotel for the Birds (presumably before the artist got wind of Ken's ban on pigeons in the square).

I did eventually make it to the Picasso exhibition, which was also well organized.

Most refreshing and thought-stimulating were some of the perhaps less well-known or at least less clichéd works, such as the late variations on Velazquez, Monet, Van Gogh, and others.

'Imitation as the source of creativity' - it occurred to me - is only the art historian's clichéd sublimation of Deleuze's far more subversive proposition: that the truly new only ever emerges in repetition. Newness is by definition an effect of repetition, of return, of grasping an 'old' thing from a different angle: which is why only repetition produces the truly singular, and no two grains of sand are ever the 'same', cannot be reduced to the same thing - this one is this one and that one is that one - even if their molecular structure is identical.

Rather than being a return to the classical tradition (as suggested by some of the accompanying material), Picasso's explorations of his later years are only a more explicit way of stating what the underlying message was all along: neither a break with the past nor simply a continuation of it, but an incessant search for the new - the excess of innovation - through more and more radical forms of repetition.

It is not enough to say that if we do not know history, we are doomed to repeat it; or the inverse, 'you can't repeat the past'. Nor is it simply the opposite, the ancient wisdom of repetitio est mater studiorum. Each of these propositions falls short. Much more subversively, one must repeat in order not simply to learn but to transform and overcome the existing. One must repeat, in order to avoid replication: repetition is never repetition of the same. To repeat is always to repeat a problem, a possibility, a fork in the road. No wonder the most original artists and improvisers in any discipline are also the greatest imitators.

Some of Picasso's morbid imagery (cubist or otherwise) throws up a related problem: what Heidegger calls the 'hiddenness' of things. The cut-up and mix of objects and perspectives - the simultaneous presentation of profile and frontal views of faces, the back and front of a torso - is an index of the impossibility of seeing things in their completeness; not a 'cubist' or 'abstract' representation of reality but the marker of a representational void.

A part of things always remains hidden from view; and even the multiplication by a mirror remains only that - a multiplication of two-dimensional perspectives which never merge in a single perspective.

What makes these images morbid is their emphasis on the tension between a three-dimensional space and the impossibility not only of representing it, but of even seeing more than two dimensions; the suggestion being that the world would probably look very different, morbid even, in three dimensions. As Picasso himself put it, "Art is a lie that makes us realize the truth."