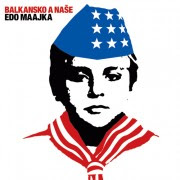

I received an e-mail recently from a Bosnian painter friend who lives in the states, with a link to the review of a new album by Bosnian rapper Edo Maajka. (think Eminem, Balkan-style...'Maajka' is a play on 'majka' - 'mother' - so...'mutha'?) The album cover, designed by Ideologija ('Ideology'), a collective based in Sarajevo, depicts a boy wearing a blue cap and red scarf, trademark of the pioniri - Tito's pioneers, a communist youth group we all took part in at school in ex-Yugoslavia - photoshopped in the colour pattern of the U.S. star-spangled banner.

Namik (that's my friend's name) sent me the link (www.menart.hr/index.php?news_id=4396) asking if I could tell who was in the picture. I thought perhaps it was one of his own paintings, and that perhaps the boy was he himself, since he often uses photos as source material for his paintings. (There is even a painting of me playing guitar somewhere in his collection...)

As it turns out, it had nothing to do with him - the photo is of a mutual friend of ours, Emir, who knew nothing about it. None of us did. Mr. Maajka presumably stumbled upon the photo on the internet, perhaps on Emir's home page at Rice University where he is a postdoctoral research fellow in computer science - homepage.mac.com/pasalic/p2/personal.html - and decided to app-RAP-riate it for his album cover. Perhaps he googled 'pionir' and it came up in the image search - the name of the file is pionir3.gif. In fact, when I performed the same google search, I found his image on another totally unrelated site - sistermadeleine.blog.hr.

Maajka's album, titled 'Sjeti se' - 'remember' - in the pre-release phase, is now officially released as 'Balkansko a nase'. ('Balkan but ours' - doesn't really make sense in literal translation, can't explain here).

It just so happens that a conversation I had recently (before Namik's e-mail) over dinner with a friend in London reminded me of an article published last year in Harper's magazine concerning art, politics, and copyright. ('On the Rights of Molotov Man: Appropriation and the Art of Context', February 2007) Being employed in the art world, my friend mentioned she was reading a law book on art and copyright, so I shared some of my own thoughts as a law grad and later sent her the article - and in the process re-read it myself.

The piece, culled from a symposium held at NYU last year, takes the form of a conversation between two artists, painter Joy Garnett and photographer Susan Meiselas, concerning a past copyright dispute between the two. Garnett had inadvertently plagiarized a celebrated photograph taken by Meiselas of a Nicaraguan Sandinista rebel lobbing a grenade at one of the last outposts of the Somoza regime, and had used the resulting painting on the announcement card for her new exhibition. After some threats from Meiselas' lawyers and informal squabbling, Garnett dropped the image from the announcement cards, which led to an all-out internet war in a solidarity campaign with her use of the image after she posted comments asking for advice on rhizome.org. The story went global and pretty soon bloggers and artists around the world began posting their own appropriations/renditions of the same image elsewhere, many speculating that Pepsi was behind the threatened lawsuit because of the bottle used for the molotov cocktail in the photo. In the end, Meiselas never sued and they came to an understanding.

In the Harper's article, Garnett concludes her contribution with the question: 'Who owns the rights to this man's struggle?' Meiselas turns this claim around, insisting that it is precisely her subject's struggle that is at stake for her, that what she resents about the appropriation and decontextualization of the image is precisely its reduction to an 'abstract riot':

'My own relationship to this picture obviously is very different from Joy's. No one can "control" art, of course, but it is important to me - in fact, it is central to my work - that I do what I can to respect the individuality of the people I photograph, all of whom exist in specific times and places. Indeed, Joy's practice of decontextualizing an image as a painter is precisely the opposite of my own hope as a photographer to contextualize an image.'

So she provides the context for 'molotov man' Pablo Arauz, telling his story, and along the way recounts various other appropriations of the same image she has tolerated in the past, from matchbox covers celebrating the anniversary of the Sandinista revolution, to the cover of a magazine published by the Nicaraguan Catholic church (they noticed 'molotov man' was wearing a crucifix), to sprayed-on stencil graffiti in a Sandinista recruitment campaign - and even down to the Contras themselves in a recuitment campaign against the Sandinistas. She concludes on the following note:

'There is no denying in this digital age that images are increasingly dislocated and far more easily decontextualized. Technology allows us to do many things, but that does not mean we must do them. Indeed, it seems to me that if history is working against context, then we must, as artists, work all the harder to reclaim that context...I still feel strongly, as I watch Pablo Arauz's context being stripped away - as I watch him being converted into the emblem of an abstract riot - that it would be a betrayal of him if I did not at least protest the diminishment of his act of defiance.'

Inspired by these words, I decided in this post to reclaim my friend Emir's context, following the careless app-RAp-riation of his image for Edo Maajka's album cover, turning him into a poster-boy for some kind of new-fangled whiteboy rap cultural critique of post-communist Balkanism. Emir, who hails from Prijedor, Bosnia (scene of the most notorious concentration camps for Muslim prisoners during the war) is a genius, if I ever met one. Think Zizek to the nth power (beard and gut included), with (proportionally) more jokes and less Lacan and Hegel. And more poetry. And totally unknown.

In Emir's own words:

'The Young Pioneer, having sworn an oath that involved hard work, study, and general if vaguely defined benevolence toward one's fellows, finds himself in Texas some twenty years later. Point A. Point B. And along the way: goetterdammerung of Brotherhood and Unity, war, exile, friendships and books, families of choice or of necessity, "new countries, new idiocies of men or of the gods."'

I would only contest Emir's loyalty with regard to the first part of the oath in question. I lived with Emir for about a month at his bachelor pad in Beaverton, Oregon (a post-industrial quasi-suburb of Portland) and found him to be an inveterate slob, even by my own fairly lax standards. When I arrived, apart from the general chaos in his tiny flat and the fact that - literally - every single dish in the kitchen was dirty, there were pots with leftover rice and beans on the stove, unrecognizable for the layers upon layers (I mean it) of multi-coloured mold growing on the inside. A micro-cosmos unto itself. The living room coffee table was piled high with stacks of dirty plates, cups, utensils and candy wrappers, and there was not a square inch of the floor or carpet visible for miles around from all the clothes, books, papers, and random paraphernalia strewn about. In the evenings he would come home and for weeks on end consume only a box of satzuma oranges for dinner until either he or I gathered up the courage to wash up.

Apart from that, the rest is more or less true and he has held his oath to Marshal Tito without exemption.

As for music, although Emir did on one occasion, years ago, submit me to a Maajka-listening session and even knew many of the rapper's lyrics by heart, his eclectic taste can hardly be summed up. If you didn't know him and you heard him playing Bach on the piano, you might be slightly jarred to also hear him rapping along to Public Enemy's 'Fear of a Black Planet' or 'Anti-Nigger Machine' while driving the beat-up old Toyota Corolla which we had to do minor claptrap repairs on from time to time. In both cases, he played and rapped with gusto.

And it is owing to Emir's frequent unannounced visits to the duplex my ex and I shared in Portland, and his temporary appropriations of my computer during these visits for the purpose of 'sailing under the flag of piracy', that my digital music collection includes items as varied as Leningrad Cowboys, Italian songsters Conti and Guccini, Beastie Boys, Weird Al Yankovic, a small compilation of Welsh folk choral music (including a rendition of the Welsh national anthem), and about ten different versions of 'Waltzing Matilda' by everyone from Tom Waits to Harry Belafonte to a choir performing it as the Australian national anthem.

Again, in his own words:

'I once categorically declared: "I don't like music. Of any kind. Period." But that was under duress. So, I do like music, all kinds. I'm a big fan of Karen Zoid, They Might Be Giants, Lou Reed, and, of course, the amazing tractor-driving superstars that make the tundra rock and make the Ulan Bator girls scream, the Leningrad Cowboys. In classical music, I have a great weakness for the renaissance masters, especially Palestrina [my Dum Complerentur in the shower makes the shrubbery wilt for miles around]. Also, somewhat soppy, I know, but Bach's passion oratoria are the coolest. Oh yeah, and Shostakovich's 8th Symphony, though I could never do it justice in the shower.'

Well, that's about it for now. I only wanted to expose the reduction of Emir's image to the post-Communist emblem of an 'abstract pionir' of the Brave New Balkans and protest the diminishment of his act(s) of defiant and subversively profound laziness, taken out of context in the service of a new-fangled critique of a new-fangled Balkan society. Nobody owns the rights to the fungous micro-cosmos that once blossomed on the stove of his bachelor flat in Portland - but neither does anyone have the right to strip it away from his image without protest and re-appropriation.

Wednesday, 19 March 2008

Six degrees of separation and the art of ap-RAP-riation

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)